Governments can make carbon more expensive too. The Climeworks founders told me they don’t believe their company will succeed on what they call “climate impact” scales unless the world puts significant prices on emissions, in the form of a carbon tax or carbon fee. “Our goal is to make it possible to capture CO₂ from the air for below $100 per ton,” Wurzbacher says. “No one owns a crystal ball, but we think — and we’re quite confident — that by something like 2030 we’ll have a global average price on carbon in the range of $100 to $150 a ton.” There is optimism in this thinking, he admitted; at the moment, only a few European countries have made progress in assessing a high price on carbon, and in the United States, carbon taxes have been repudiated recently at the polls, most recently in Washington State. Still, if such prices became a reality, they could benefit the carbon extraction market in a variety of ways. A company that sells a product or uses a process that creates high emissions — an airline, for instance, or a steel maker — could be required to pay carbon-removal companies $100 per metric ton or more to offset their CO₂ output. Or a government might use carbon-tax proceeds to directly pay businesses to collect and bury CO₂. In the absence of any meaningful government action, perhaps a crusading billionaire could put all the money in his estate toward capturing CO₂ and stashing it in the earth.

So, since 2014, two-thirds of the tap water and one-third of the total water supply in Beijing, in the arid north, has come by canal and pipeline from a reservoir 1,400km to the south, fed by a tributary of the Yangzi. China hails the project as an unqualified success, supplying more than 50m people in its early years of operation. And it is part of an even bigger project that will see up to 45bn cubic metres of water a year transferred—7% of Chinese consumption. Environmentalists and water experts at home and abroad are more sceptical, however. Mr Biswas at the Lee Kuan Yew School in Singapore says the project gives China at best “a few years’ grace”. The worry is that it is a distraction from more pressing and important policy changes—cutting demand for water—and may actually encourage wasteful use. As elsewhere, the authorities fear that charging users for the true cost of their water might provoke protests and threaten social stability.

Woskov asks, “What if you could drill beyond this limit? What if you could drill over 10 kilometers into the Earth’s crust?” With his proposed gyrotron technology this is theoretically possible.

In one hand, senior research engineer Paul Woskov holds orange water cooling lines that lead to the rock test chamber (left foreground), and in the other the result of drilling rock with a gyrotron beam.

© Faversham House Group Ltd 2019. WWT and WET News news articles may be copied or forwarded for individual use only. No other reproduction or distribution is permitted without prior written consent.

Drilling is generally carried out in two stages, the first to install the permanent casing and then the final drilling to completion depth. In cases where there is some uncertainty about the geology, a field geologist should be on hand to determine where casings should be set and the final completion depth.

The scanner then picks up an angular object, one that could be an anchor. If it is indeed an anchor, and from prior to 1795 when the Money Pit was discovered, it could help solve the Oak Island mystery. In the end the team conclude that they definitely saw some anomalies, and are eager to see what transpires once the data is processed. If the data yields promising information, the next step is to put a diver in the water.

Gold mineralisation at Kalanako has been modelled at a threshold of 0.2 ppm Au with a minimum thickness of three metres down-the hole (equivalent to two metres vertically) into 34 wireframes (of which six represent two-thirds of the total mineralised volume). The mineralised wireframes are considered to be a single domain and have an average thickness of seven metres.

"That was it, that’s what I saw in my dream," he recalled, tearing up. "That’s when I knew that this was supposed to happen."

A man narrowly avoided being crushed by falling bricks from a collapsing building during the weekend’s strong winds.

But what isn’t apparent at first glance are the millions of people across the globe who now have access to clean water, all thanks to this prototype.

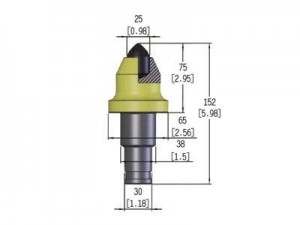

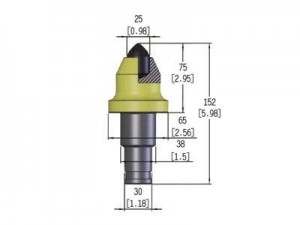

Powerbit is the all new range of tophammer drill bits for surface drilling from Epiroc Drilling Tools. They’re built to take on any rock, from hard to soft, and from abrasive to non-abrasive. These bits last much longer. They give the drillers more meters before the first regrind, and many more meters between the regrinds. With Secoroc Powerbit, drillers are guaranteed to get more performance from each bit.

red-rock-probes-inch-cape-waters – reNews | Rc Dth Hammer Related Video:

, , ,